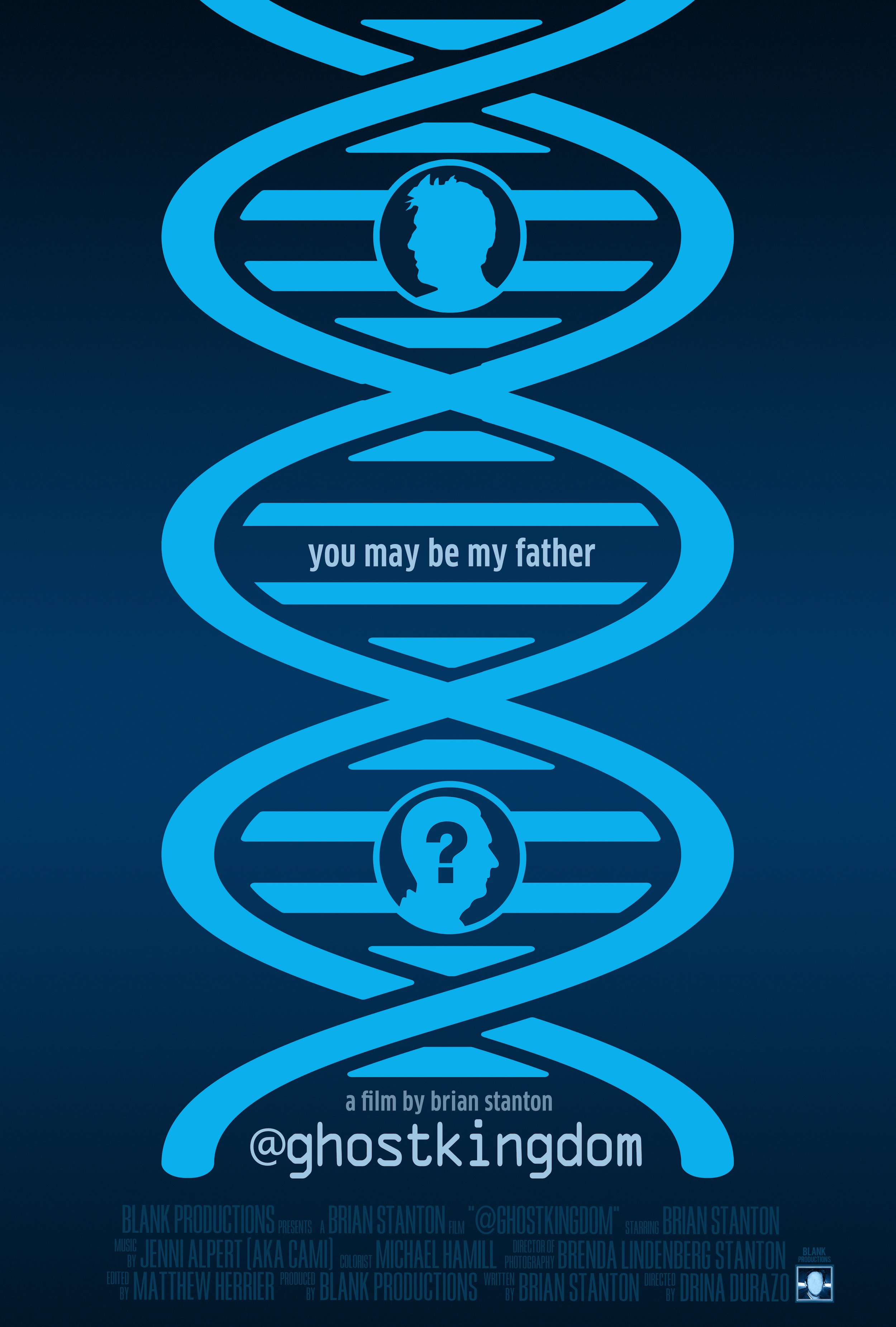

Possible Fathers, Possible Worlds:

Brian Stanton's @ghostkingdom

Spoiler Alert: The following chapter discusses Brian Stanton’s film, @ghostkingdom, at length and assumes that the reader has engaged with the film in its entirety. To learn more, visit atghostkingdom.com and rent the film on Vimeo.

Inspired by Betty Jean Lifton’s presentation at the American Adoption Congress Conference in 2007, Brian Stanton’s film @ghostkingdom draws on Lifton’s Ghost Kingdom theory through the main character’s attempt to reunite with his father. Stanton’s film provides an autofictional example of Lifton’s Ghost Kingdom. His film portrays how adoptees reconcile truth and fiction: how, in the absence of their biological truths, they live simultaneously in many possible worlds in addition to the actual world. Explicitly named after Lifton’s theory, Stanton’s film illuminates a gray area between fiction and reality where impossible scenarios can also be true when they serve the purpose of filling in a gap of crucial self-knowledge. The implications of possible worlds theory suggest in this case study that while an adoptee may construct fictional characters and possible worlds to fill in gaps, those fictions also work to inform an adoptee’s reality. In this way, fiction and reality work together instead of as opposites. Therefore, this film effectively portrays the use of fiction as a necessary cognitive process that aids in building identity and giving narrative order to a person’s life.

In the film, Brayden is an adoptee in mid-life with a wife and children. Fifteen years prior to the plotline, he searched for and found his birth mother, but after being in reunion and establishing a relationship with her, he decides to also seek out his father. The film opens with the scene of a graveyard and a voiceover borrowed from Lifton’s presentation at the American Adoption Congress Conference in 2007, explaining what the Ghost Kingdom is, who resides there, and why adoptees must “cross over” into the Ghost Kingdom. As Lifton says, the Ghost Kingdom is “the land of the ‘as if’ dead” because these ghosts are not dead like any respectable ghost is.” Her voice over ends with, “when we go and search, we have to cross over into the Ghost Kingdom” (Stanton). The story is therefore poised from the beginning to focus on the “crossing over'' aspect of the Ghost Kingdom concept, which is the part of an adoptee’s journey where they begin actively searching for the people represented by the ghosts in their psychic realm. Armed with anecdotal recollections from his birth mother, access to mail-in DNA test tubes, and the internet, Brayden considers four major possibilities of who his birth father might be. Throughout the film, Brayden leaves emails, voicemails, and text messages to his suspected (and often unsuspecting) biological relatives. He communicates with two possible fathers (and one possible sister) and, as he does, depicts the creation and destruction of the expectations he brings to each potential relationship. This film raises awareness about and reveals what it is like to be an adoptee in search of roots, reunion, and biological truth.

Heroes and Scapegoats in Ghost Kingdoms

As created by Lifton, the Ghost Kingdom theory has three major parts: the development of ghosts in periods of stasis, the movement towards seeking out truth often through search and reunion, and the reconciliation between the ghosts and whatever reality is found. Though overall this film focuses on Brayden’s movement beyond his reunion with his mother as he searches for his father, we do get a glimpse at his childhood Ghost Kingdom to see how it served him. In a monologue addressed to his presumed dead father’s gravestone, Brayden talks about the fantasy ghosts of his biological parents he had as a child, back before he even had the plans or the means to move towards finding them. In his monologue he explains, “I’ve always fantasized about you, who my father is, who my mother is” (Stanton). He goes on to say, “If I was ever pissed at my adoptive parents, I dreamed my perfect, beautiful biological mother was going to save me and take me away,” but on the flipside, if he was angry at his birth mother, “she was just an ugly, trailer trash, fucked-up drug addict who couldn’t even take care of her own little boy” (Stanton).

These opposing daydreams represent different possible worlds. In Marie-Laure Ryan’s chapter, “From Possible Worlds to Storyworlds” in her and Alice Bell’s book Possible Worlds Theory and Contemporary Narratology, Ryan explains that fantastic stories, which we can categorize as imagined daydreams with relative safety, “may not be actualizable in the real world . . . , but they remain imaginable and logically consistent. PW [Possible Worlds] theory would regard their worlds as possible” (Bell & Ryan 66). The fantasy ghosts he describes of his birth parents are, in themselves, possible worlds because while their existence might be improbable or even impossible, they are still technically possible because they are imaginable. Because his Ghost Kingdom allows the young Brayden to cope with his external reality by either daydreaming about his birth parents as heroes or scapegoat, the process of creating this fluid Ghost Kingdom is a cognitive one and directly contributes to his identity. The Ghost Kingdom shows the liminal space between lived reality and fantasy in a situation where fantasy fills in missing knowledge of the self.

Though these are not the full sum of possible worlds depicted in the film, they do introduce the question the film circles around which is: Who is my father? As Brayden works through his search, virtually meeting possible relatives and taking DNA tests, viewers experience the dissonance between Brayden’s fantasies of what his biological family could be and what he actually finds to be true.

Furthermore, the film uses the Ghost Kingdom theory itself as a narrative framework, creating possible worlds to portray the liminality of adoptee experiences by emphasizing the role of fictional possibilities in an otherwise real life situation. In other words, the Ghost Kingdom is an imaginary world, a psychic space, where lost and wished-for characters are created. By implementing the structure of Lifton’s Ghost Kingdom theory, the film provides a new avenue for exploring how such a narrative structure might blur the line between life-writing and fictional writing.

Autofiction

In a post-screening conversation during AKA’s 2021 Elevation Conference, Brian Stanton explained that the plotline is also based on an experience he had during his actual search for his birth father in which he formed an online relationship with a woman he thought was his sister (“Elevation”). Knowing even a little bit about the artist responsible for the film can help illuminate the motivations behind the storyline and, for the purposes of this research, explain just how tangled the web between reality and fiction actually is.

Thanks to Stanton’s explanation, we know that even though the film itself is fictional, it is loosely related to the author’s experience. This is a common occurrence in both Ghost Kingdom narratives and adoptee narratives at large. Adoption is such an intimate family experience; as such, it is often difficult to share about a particular experience, especially the ones tinged so heavily with grief, without also sharing the intimacies of other family members’ experiences. In many ways, fictional depictions of adoptee experiences are a safe and more veiled route to sharing the story without hurting anyone’s feelings. That being said, fictional narratives are in no way a cop-out; in so many ways, they free the author to pursue expressing the arguments they want to make in bolder and more artistic ways. This is true for Stanton’s film.

The film’s loose foundation in reality is not the only aspect I want to focus on. Ghost Kingdom narratives themselves play with the concept of reality and fiction because in the actual world, adoptees create Ghost Kingdom fantasies as a way to self-soothe, comfort themselves, or even escape reality momentarily (like a good book). Without access to what Brayden calls “my truth” in the film, adoptees are left with holes in their life narratives and their identities. Yet these fantasies—constructed to fill these emotional gaps—are not simply fictional escape methods. Rather, depending on the adoptee and how much information they do or do not have about their specific adoption situation, the Ghost Kingdom they construct for themselves also works to inform their concept of identity. In this way, the fiction affects the reality.

The film takes place in a time and space that is recognizable to the audience as a mimetic depiction of reality. Everything about the setting aligns with the actual world; Brayden could be Mr. Every Adoptee in the sense that many adult adoptees have some of the same desire to better understand their genetic history in order to build their identities, and he makes use of his phone, computer, and internet in order to seek out that genetic history.

There is even an allusion to the current political turmoil in America when he and his possible sister make reference to blue states and red states. Because of the way the film fictionally depicts a plotline that could be possible in the actual world and is also structured around real-life experiences, even if they are not what some might call true like a memoir, it can be helpful to define this piece as autofiction. As defined by Alison James, autofiction is a kind of fiction about the self. While scholars still debate whether it falls more squarely into the life-writing camp (because of the “auto” which refers to the self) or the fiction camp, I am primarily interested in how autofiction allows “for a range of configurations of the fact/fiction relationship” (42). As a result, defining this film as autofiction points toward the ways that the film is a piece of realistic and mimetic fiction that, while reflective of a real adoptee’s experience, employs a considerable distance in order to freely demonstrate the complexities between fiction and reality through a fictional character’s experience.

Truth and Language

The opening of the film reveals the title’s significance. During this sequence, Brayden reaches out to possible relatives via email, social media, and phone calls. As is common with online messaging systems of all sorts, prefacing a username with the @ (at) symbol usually functions as a way to initiate contact with somebody. In this case, Brayden is reaching out to his Ghost Kingdom ghosts by whatever means he can in order to find his birth father.

The allusion to internet communication emphasizes both the way the internet has revolutionized how adoptees seek reunion with their biological families and the way in which such connections can often feel foreign or distant. As Brayden explains to one of the people he contacts, “I’m simply seeking my roots, my genetic heritage, my medical history, and . . . my truth” (Stanton). Braydon’s emphasis on truth reveals a crux of the film as it explores the tensions between biological truth and legal truth. Legally, in adoption, biological relationships are severed, original birth certificates are sealed, and the adoptive parents are recognized as the adoptee’s parents, even on the amended birth certificate. This legal act effectively erases the birth parents completely and creates a fictional reality, in a sense, because the amended birth certificate shows the adoptive parents as if they gave birth to the child.

However, the act of searching defies the legal contract and fictionalized legal truth of adoption because a search emphasizes the importance of biological relationships. The concept of truth as it is portrayed in this film relies heavily on the idea that biological truth is superior to legal truth, especially as it pertains to Brayden’s identity. There are simply some things that, without access to generational memory, medical history, or even likenesses between family members, are essentially missing in a person’s identity formation process. The distinction of biological truth in this film is important because it pushes back on the cultural assumption present in mainstream perceptions of adoption that “love is enough” to make a family. When adoption agencies or adoptive parents say this, what they mean is that simply providing an adoptee with a loving family is enough, when actually they are minimizing the genetic component of the adoptee’s identity.

One significant scene in the film emphasizes this by referencing the idea of genetic mirroring. Genetic mirroring is a more recent explanation of what one psychiatrist, E. Wellisch, discussed in a 1952 Journal of Mental Health article. In Wellisch’s article, he states, “Knowledge of and definite relationship to his genealogy is therefore necessary for a child to build up his complete body-image and world-picture. It is an inalienable and entailed right of every person” (41). In other words, the lack of biological relatives with which to compare the self to, creates a strongly felt absence. Before the term genetic mirroring, even Max Frisk explained a concept much like it when he argued that adopted teens needed to meet their biological parents in order to deal with what he called “hereditary ghosts” (Frisk 9).

In the scene, Brayden is talking to Keely, his possible sister, about physical characteristics. He sits in the front of the mirror and analyzes his looks, attempting to see if maybe he does have family traits as she describes them.

In this way, he is holding out hope that Keely is in fact his sister. Genetic mirroring is a vital aspect of growing up that adoptees specifically miss out on, so as Brayden tries to connect to Keely by comparing physical traits, he is also attempting to recover what he has lost through his adoption. As he does so, he is building yet another possible world in which he is related to Keely and her father, Max, the federal inmate. The reason he is compelled to create such a possibility is because of the lack of biological truth he has access to about himself. From what the audience can glean about his childhood, he knew his adoptive parents and he knew about his adoption, but not in full. In this way, knowing and not knowing, Brayden lived in a reality bolstered by internally created fiction for many years.

Related to both the ideas of biological truth and of fictions in adoptee narratives, scholars of adoption often point to the fictive language present in descriptions of the adoptive family, saying that the adoptive family is, itself, fiction, and therefore, the language that demonstrates truth is that of the “real” or biological family. Marianne Novy explains that “adoption has repeatedly been called a fiction of parenthood,” and goes on to note the contrast between “considering adoption itself as a fiction in the sense of pretense, or constructing it as something that should imitate the traditional biological family as closely as possible in appearance, in the so-called ‘as-if’ family” (4). The language surrounding adoption can be problematic and reflects the narrative complexities inherent in adoptive families because when the word “real” is employed to signify the biological parents, does that mean that, in contrast, the adoptive parents are “fake?” Equally problematic is when adoptive parents insist that they alone are the adoptee’s “real” parents by emphasizing the fact that they have raised the child. This attitude effectively silences what is also true, that the adoptee has another biological family. Amidst all this, adoptees are left to figure out or define for themselves who their real family is and how to voice that, often worrying about how to do so without deeply offending other parties.

It is necessary, then, for us to also investigate how adoptees create their own fiction, often opposing from other family members. These fictions are necessary for adoptees to shape their reality and they do so by retreating, as it were, to a fictional psychic realm in order to escape momentarily from their lived reality, which could be itself, arguably, a fictive environment based on the language claiming opposing realities that surrounds it. The fictions that adoptees themselves engage with are often primarily focused, not on which parent pair is “real,” but instead on the truth of their origins, most often in story form. Margaret Homans argues that adoptees look towards their origins, but because their origins are often unknown, there is “the common tendency to address that problem with fiction making” (5). She goes on to say that “adoption stories can demonstrate the creative lengths to which it is possible to go . . . in the endeavor to make or reconstruct an origin” (23). It is in this way that adoptees seemingly engage in fiction making of their own to fill the gap of an irretrievable past.

Where scholars such as Novy and Homans have focused on language in adoption and the fictions that spring from such situations, no one has examined at length how exactly the fictions adoptees create during their lifespans shape their realities. This is precisely the purpose a Ghost Kingdom serves. Despite external forces disagreeing about an adoptee’s reality, an adoptee can retreat to their Ghost Kingdom to play out the possibilities of what their reality could be. These counternarratives and possible worlds, then, serve as a substitute for what is missing in their lives and can be readjusted as necessary as an adoptee progresses through life. This readjusting is especially important as an adoptee moves beyond the stasis of the Ghost Kingdom into both the search and, if all goes well, some kind of additional information about one’s circumstance.

Possible Fathers, Possible Worlds

The most prominent interpretation of Lifton’s Ghost Kingdom theory and example of possible worlds in @ghostkingdom is the strong focus on the idea of “crossing over” into the Ghost Kingdom via seeking out reunion or, in other words, the act of willfully shattering the previously established fantasy of biological relatives by meeting said relatives in reality. In his search to find his birth father, Brayden must sort through the information available to him which points to four possible fathers. In preparation for making the discovery he hopes for, Brayden creates four internal possible worlds revolving around each of these possible fathers. These possible worlds adjust as he takes new possibilities into consideration as new information presents itself to him during his search.

For a long time, fifteen years at the very least, Brayden had a clear depiction of his birth father's ghost, thanks to his birth mother's anecdotal account. He discusses during a monologue at a gravestone how difficult it has been for his mother, being asked to revisit such a traumatizing past of both rape and relinquishment. For quite some time, her traumatic past and the idea of potentially making her revisit it is one of the reasons Brayden prevents himself from seeking out his birth father who could potentially be a rapist. The other reason is simple: Brayden is not interested in meeting a man who most likely raped his mother, which is completely understandable. Because there was previously an absence of story in the place where Brayden’s birth father was concerned—not counting, of course, Brayden’s childhood fantasies of his birth father—he readily accepts the story from his birth mother that whoever his birth father was, his conception was not a pleasant moment filled up with heartwarming love. But eventually, as time goes on and after the relationship with his birth mother has settled into familiarity, he realizes that he still needs to seek out his birth father, rapist or not, in order to fully know his biological truth.

Absence by Greg Santos

Greg Santos is a poet, editor, and educator. He is an adoptee of Cambodian, Portuguese, and Spanish heritage who currently resides in Montreal. You can find more of his work on his website.

The result of this search is the blossoming of not one but four possible worlds because, as he finds out from his birth mother, there were three men who raped her at a party, which was around the time he was conceived and, as he later finds out, a summertime boyfriend from around the same time. Each of the possible fathers–the summertime boyfriend, federal inmate, an unnamed guy from the party, and the guy who is already under a headstone–represent four primary examples of possible worlds.

Each possible world constructed is a fiction built on a sliver of truth that is, at once, both impossible until proven true, and yet very real for Brayden, so real in fact, that the fiction in question directly affects how he engages with his reality. The sliver of truth in the first example of a possible father actually contains two possibilities, the first of which is Jim. In the very first graveyard scene, Brayden tells Jim’s headstone that his mother told him “about that night at the party, where you, your ol’ buddy Max, and some other I-don’t-know-who decided to have some extra-curricular [sic] fun with an impressionable younger coed during a night of debauchery” (Stanton). Neither Max nor Brayden’s birth mother know this other possible father’s name, which is why this first possibility is such a complex scenario. Brayden goes on to tell the gravestone that Max has given his side of the story already, saying that his birth mother was not forced, but that he is inclined to believe his birth mother. In the possible world in which Jim is Brayden’s father, Brayden must accept two simultaneous possibilities. First, that if Jim is not his father, the third unnamed man must be and without his name, he will probably be unable to find him. At least, it will be considerably harder. Second, since the rest of Jim’s family he attempted to contact is not interested in corresponding with him, he may never get confirmation that Jim is actually his father. He bemoans this possibility by saying, “Fuck, I tried. You’ve no idea. I contacted your kids, Jennifer and Patrick. Talked with your brother Travis. He actually agreed to take a test with me but changed his mind at the last minute” (Stanton). If Jim is his dead father, there are answers Brayden might never receive about his conception or half of his heritage. The same is true if the unnamed man is his father. Thus, the ghost of what could be threatens to remain stagnant and Brayden is left with only possibilities.

As Brayden continues on his search to find his true birth father, the audience sees his different fantasies about each possibility adjusting in real-time (or, at least, real movie time) to his situation as he makes discoveries. The next possible father is Max, the federal inmate and the other person Brayden’s birth mother mentioned by name when she revealed the incident at the party all those years ago. Though Brayden does not interact directly with Max for much of the time that he considers Max a strong possibility, he does develop a friendship with Max’s daughter, his possible sister, Keely. As their friendship develops primarily online and over the phone, the audience is privy to the sometimes rapid adjustment of Brayden’s expectations as he hopes that the possible world in which Max is his father and Keely is his sister could be the actual world. Though he begins the relationship with doubts, the longer they correspond, the more his hopes inflate that they might be related. When Keely’s DNA test returns with an uncertain percentage, his doubt sets in and he apologizes to her for wasting her time. The significance of Brayden’s ever-adjusting possible worlds is important to recognize because, in the searching phase, all he is armed with is small bits of possibility which turn into hopes that he must test against reality. Unlike the ghosts of his birth parents from when he was young, these possible worlds must move with him as he learns more during his search.

After Keely’s inconclusive DNA test, Brayden gets a phone call from yet another possible father, his birth mother’s summertime boyfriend from around the same time, Dale. This example of a possible world is actually an example of a Ghost Kingdom from outside the adoptee perspective in that Dale, as Brayden finds out, spent his entire lifetime since his relationship with Brayden’s birth mother considering, even hoping for, the possibility that Brayden might be his son. As Dale explains the situation to Brayden, Brayden finds himself tearing up at the sudden entrance of a brand new possibility, especially one where his possible father has spent years hoping to welcome him into the family. Because this possibility is unexpected to Brayden, he quickly cycles through feelings, thoughts, and behaviors in response to the possibility that Dale could be his father.

We see how these moving stories, as they go back and forth between fictional possibilities and their actual world, affect the feelings, thoughts, and behaviors of someone as their internal narratives shift. This order of mental events is important to notice. First is the feeling, which is often where a possible world begins; then the person takes the time to contemplate that feeling, which is analogous to when a person considers the implications of such a possibility. Finally, after feelings and contemplations, the person can be moved towards actions and behaviors. In the instance where Dale is introduced to the storyline, Brayden cycles through all three of these stages in rapid succession. The last thing to do, after he has adjusted his hopes and expectations for this possibility, is to confirm with a DNA test. Unfortunately, it comes back negative so he is left with the task of accepting this and letting down Dale as well. This shattering of expectations is part of the third phase of Lifton’s Ghost Kingdom. She explains that after reunion (or at least coming to some new understanding about the family), “adoptees must weave a new self-narrative out of the fragments of what was, what might have been, and what is” (Lifton, Journey 259). This is no easy task, but as each possible world of Brayden’s is disproved by DNA tests, he must let go of his previous fantasy and keep moving forward in his search.

After the summertime boyfriend possibility falls through, Brayden returns to ask Keely to help him communicate with Max in federal prison. After he achieves this, the paternity test (which is supposedly the most reliable DNA test) for Max returns negative as well so Brayden must reconcile his hopes with reality. His tearful laughter at the 0% DNA results indicates how disappointed he is to have to face the scientific fact that his possible world turned out to be impossible. Finally, he has no options except for Jim, the dead man, and the unnamed man left. With all his viable options gone, Brayden returns to his imagination to ponder the only two possibilities that remain.

This film makes an important contribution to the adoption community, continuing Lifton’s conversation about Ghost Kingdoms while also providing an example of it. It both demonstrates a possible experience of a Ghost Kingdom and makes commentary on the many possibilities Ghost Kingdoms can contain and how they change over time. In order to achieve this, the film makes several assumptions about the audience, including that they are familiar with adoption community discourse, the unique difficulties of reunion, and the emotions that adoptees must learn to navigate over a lifetime. The film speaks directly to the adoption discourse community both in how it references previous collective knowledge of the adoption discourse community and how it goes about interpreting that knowledge in a new way. By portraying the Ghost Kingdom elements in a way that demonstrates their evolution from a childhood escape method and the drive to seek reunion as an adult, Stanton shows the complexity of Ghost Kingdoms through the exploration of possible worlds. Both the character and the textual actual world he inhabits are realistic fiction, and the possible worlds he creates with each expectation of every new possible father are purely fantasies yet they directly impact his emotions and behaviors. In order to reconcile the gap of information about himself, Brayden uses Ghost Kingdom possible worlds as a cognitive process to aid in building his identity and making his life narrative more cohesive. The possible worlds within this autofictional narrative emphasize a gap in knowledge about the self, thereby demonstrating how the creation of fiction can directly impact a person’s lived reality.